-

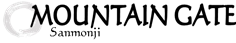

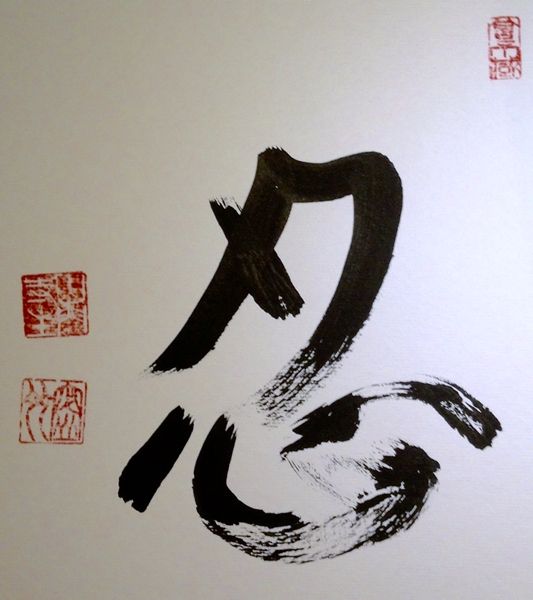

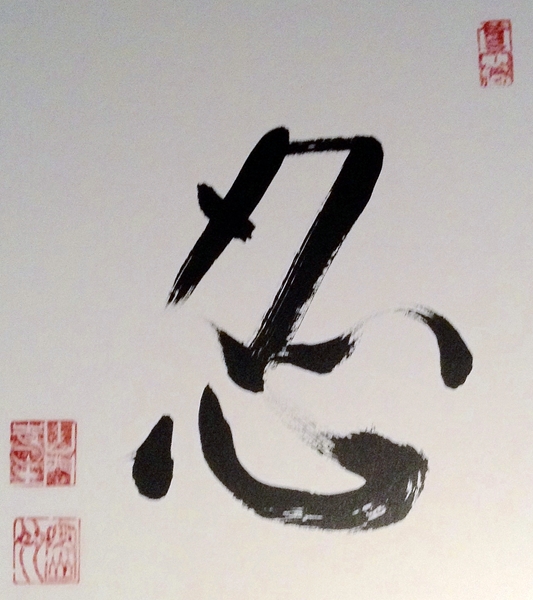

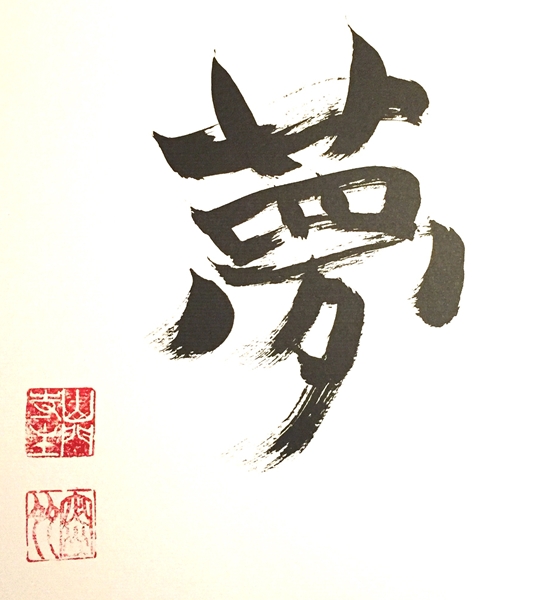

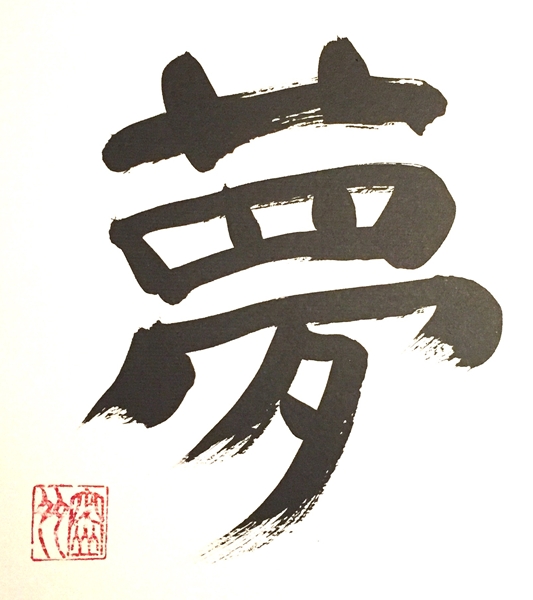

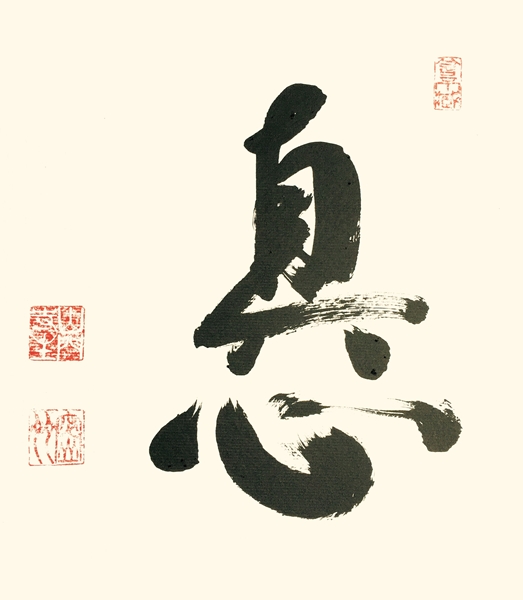

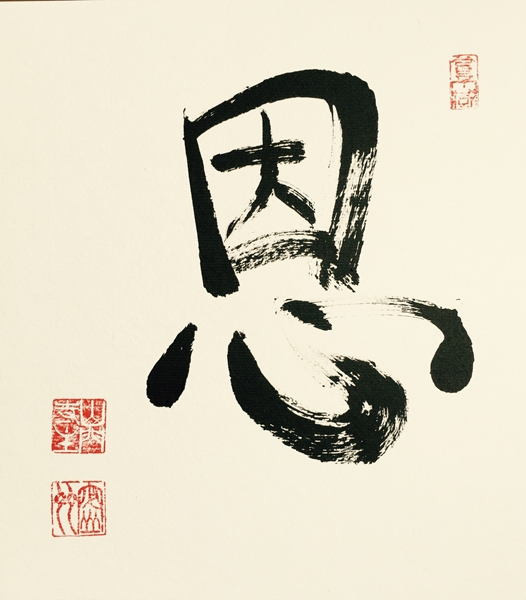

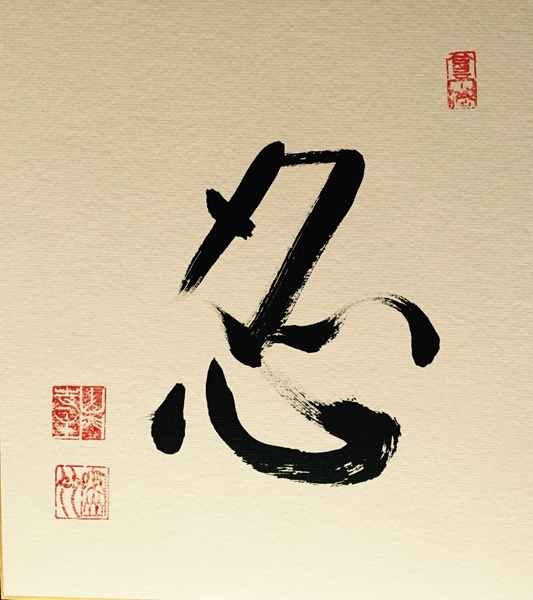

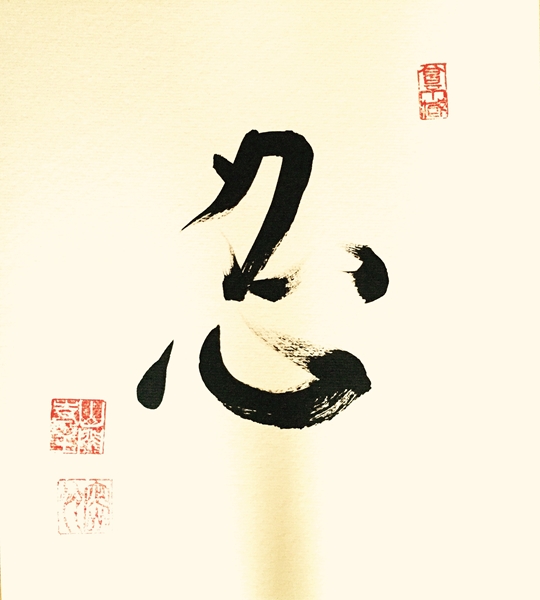

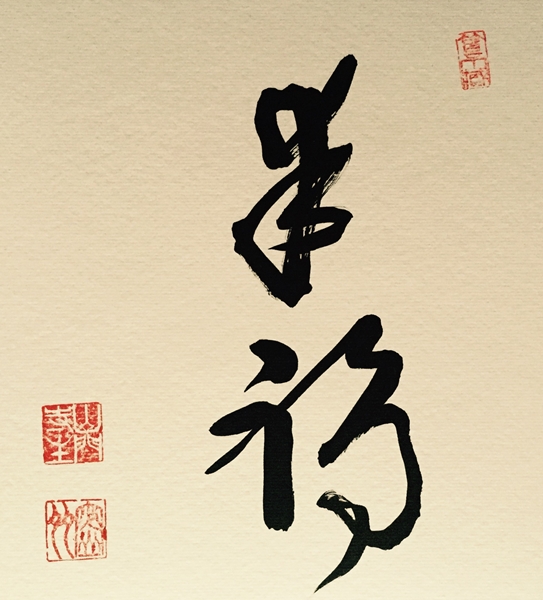

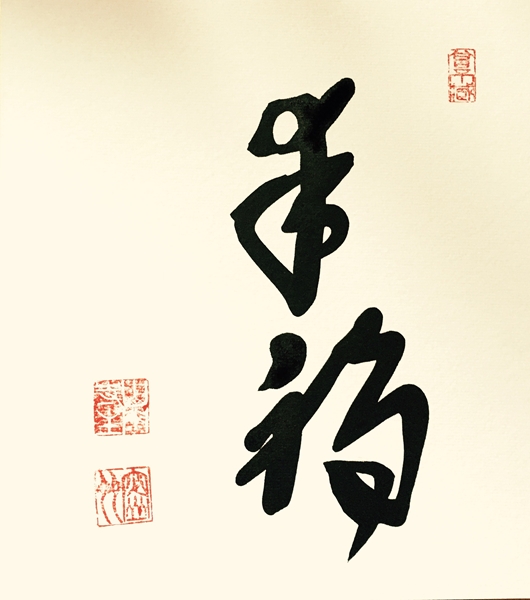

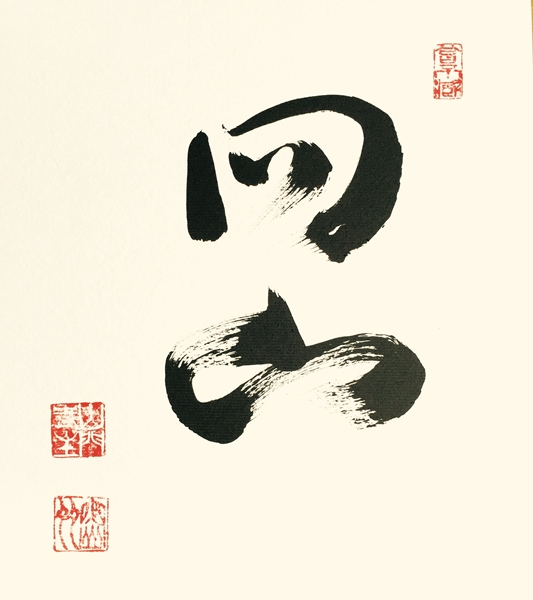

Japanese Calligraphy

“Kan ji,” or “Chinese characters,” developed over thousands of years and were eventually exported to the island nation of Japan, which had not yet developed its own written language. The Chinese characters developed out of a series of pictures that expressed concrete thought and speech. “Sun,” for example, was originally depicted as a circle with a dot in the middle; “moon” was communicated by drawing a sliver of moon partially hidden by some small clouds. “East” was a [rising] sun behind a tree.

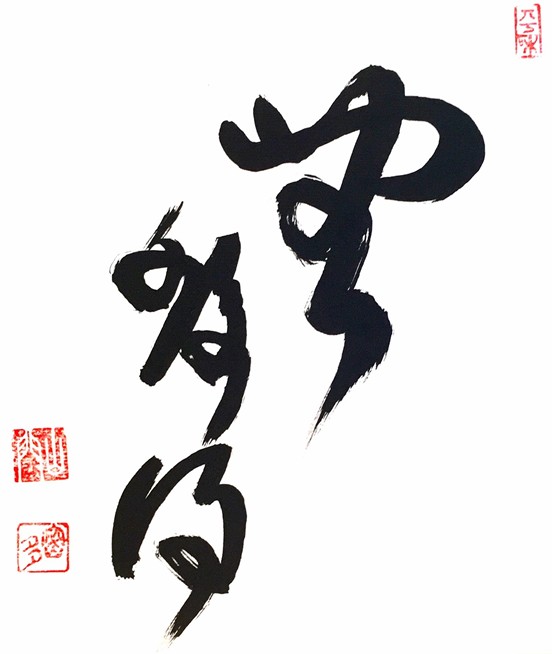

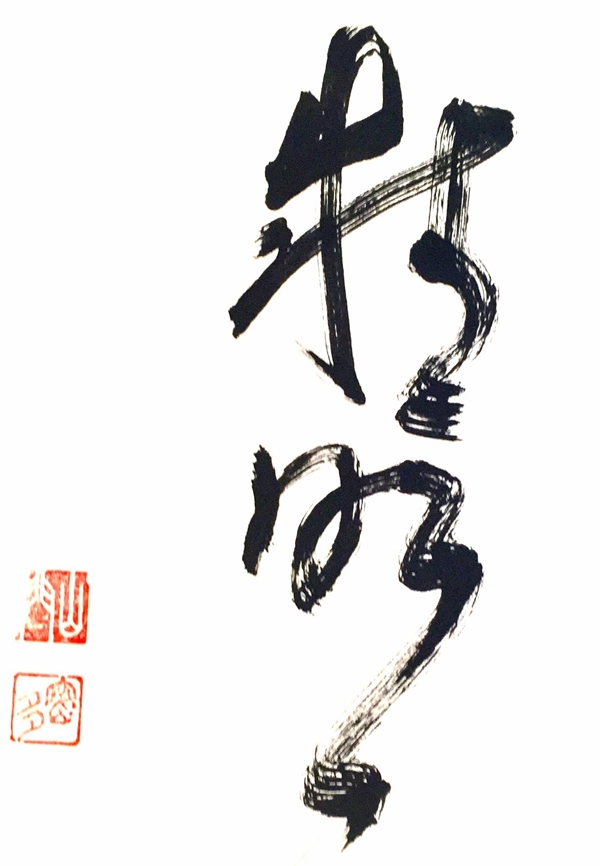

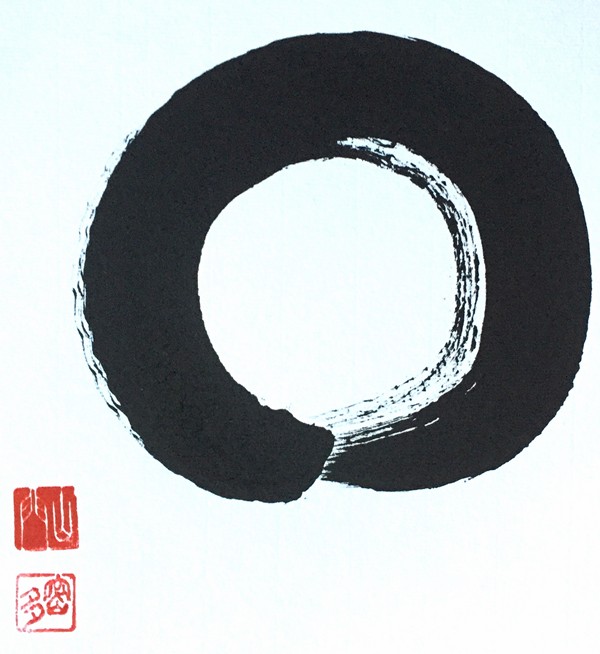

Out of these early drawings came a rich, beautiful, and highly expressive brush-written language which not only serves the Chinese but also the Japanese and, to a certain extent, the Koreans (though they also developed their own unique characters). That written language is both art and communication. Chinese Zen masters arriving in Japan communicated with their Japanese students through their mutual written language, as few could communicate orally. Zen Buddhist monks and priests were quick to recognize not only a means of speaking through brush and ink but also an effective method of pointing to our True Nature and inspiring monks and lay practitioners alike in their practice.

The famous Rinzai Zen master Hakuin Ekaku, for example, was prolific in his creation of inspiring calligraphies, often given as gifts to lay people. Further, brush calligraphy became a practice in itself for the monk or priest writing the calligraphies, for at its best it demands utter attention, complete oneness with the brush; there is no one creating a calligraphy, there is only brush dancing across paper. This is recognized in the term “shou dou”—the Way of the Brush.